Titan looks suspiciously like our own planet when you observe it. However, Saturn’s moon and our own Earth couldn’t be any more different. Where landscapes are made of silicate-based sediments on Earth, many believe Titan’s landscapes are made of solid organic compounds. As such, they should be much more fragile than Earth’s. A new study may have figured out how the landscapes on Titan came to be.

Landscapes on Titan are more intricate than you might think

From space, Saturn’s moon, Titan, looks very similar to Earth. However, when you really start diving into the landscapes that make up the moon, things get very interesting. See, landscapes on Titan might look beautiful from space. But, on the surface, the landscape is cut by flowing rivers of liquid methane, and the land itself is made up of hydrocarbons.

For years, scientists have wondered how such fragile components, like the hydrocarbons on Titan, could hold to the intense nitrogen wind and liquid methane that cover the planet. With this new study, Mathieu Lapôtre, an assistant professor of geological sciences at Stanford, and other researchers may have discovered a combination that helps keep the landscapes on Titan from wearing away.

According to the study, which they published in Geophysical Research Letters, a new model based on sintering, wind, and seasonal change could explain how the landscapes on Titan hold up over time.

Sedimentary, my dear Watson

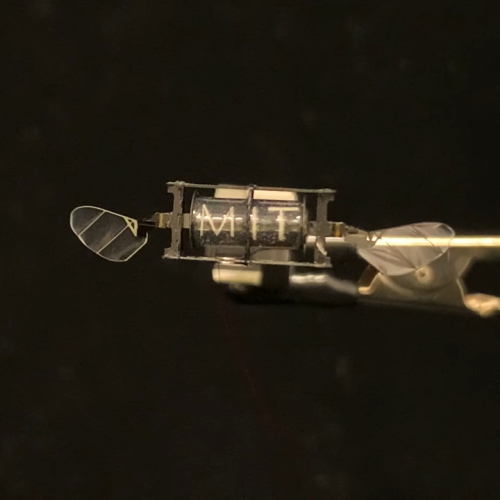

To determine how Titan’s landscapes survive, the scientists focused their efforts on sediments known as ooids. These sediments are found on Earth and are believed to be similar to the composition found on Saturn’s moon. As a result, ooids are probably the closest we’ll come to properly studying Titan’s landscapes anytime soon.

What makes ooids so intriguing is that these sediments grow while also eroding. The grains accrete material thanks to a process called chemical precipitation. Then, at the same time, the water that they live in erodes the material. This allows the ooids to maintain a consistent size.

The researchers believe that the sediments that make up the landscapes on Titan may be using a similar process. They also believe that the seasonal liquid transport cycle on Titan could play a part in how this process works, too. The researchers also posit that a similar process could have been active on Mars in the past, too.

“We’re showing that on Titan – just like on Earth and what used to be the case on Mars – we have an active sedimentary cycle that can explain the latitudinal distribution of landscapes through episodic abrasion and sintering driven by Titan’s seasons,” Lapôtre shared in a release about the study.